Zarah Leander

- Birth Date:

- 15.03.1907

- Death date:

- 23.06.1981

- Extra names:

- Zarah Leander, Цара Леандер, Cāra, Sāra, Zāra Leander; Цара Стина Хедберг

- Categories:

- Actor, Related to Latvia, Singer

- Nationality:

- Swede

- Cemetery:

- Set cemetery

Zarah Leander (15 March 1907 – 23 June 1981) was a Swedish actress and singer.

Leander began her career in the late 1920s, and by the mid-1930s her success inEurope, particularly in Germany and the Scandinavian countries, led to invitations to work in the United States. Leander was reluctant to relocate her children, and opted to remain in Europe, and from 1936 was contracted to work for the German Universum Film AG (UFA) while continuing to record songs. Leander later noted that while her films were successful, her work as a recording artist was more profitable.

As a result of her controversial choice to work for the state-owned UFA in Adolf Hitler'sGermany, her films and song lyrics were viewed by some as propaganda for the Nazicause, although she took no public political position. Leander was strongly criticized as a result, particularly in Sweden where she returned after her Berlin home was bombed during an air raid. Initially she was shunned by much of the artistic community and public in Sweden, and found herself unable to resume her career after the Second World War. It was several years before she could make a comeback in Sweden, and she would remain a figure of public controversy for the rest of her life.

Eventually she returned to performing throughout Europe, but was unable to equal the level of success she had previously achieved. She spent her later years in retirement inStockholm, and died there at the age of 74.

Beginnings

She was born as Sara Stina Hedberg in Karlstad. While Zarah Leander's career in the Third Reich has been criticized, rumors nevertheless erroneously implied that Zarah was of Jewish heritage. According to her son Göran, his mother's family, going back through generations, were from the Swedish provinces of Dalarna and Värmland.

Although Zarah Leander studied piano and violin as a small child, and sang on stage for the first time at the age of six, she initially had no intention of becoming a professional performer and led an ordinary life for several years. As a teenager she lived two years in Riga (1922–1924), where she learned German, took up work as a secretary, married Nils Leander (1926), and had two children (1927 and 1929). However, in 1929 she was engaged, as an amateur, in a touring cabaret by the entertainer and producer Ernst Rolf and for the first time sang "Vill ni se en stjärna," ('Do you want to see a star?') which soon would become her signature tune.

In 1930, she participated in four cabarets in the capital, Stockholm, made her first records, including a cover of Marlene Dietrich's "Falling in Love Again", and played a part in a film. However, it was as "Hanna Glavari" in Franz Lehár's operetta The Merry Widowthat she had her definitive break-through (1931). By then she had divorced Nils Leander. In the following years, she expanded upon her career and made a living as an artist on stage and in film in Scandinavia. Her fame brought her proposals from the European continent and from Hollywood, where a number of Swedish actors and directors were working.

In the beginning of the 1930s she performed with the Swedish revue artist, producer and songwriter Karl Gerhard who was a prominent anti-Nazi. He wrote a song for Zarah Leander, "I skuggan av en stövel" (In the shadow of a boot), in 1934 which strongly condemned the persecution of Jews in Nazi-Germany.

Zarah Leander opted for an international career on the European continent. As a mother of two school-age children, she ruled out a move to America. In her view it was, most of all, too insecure. She feared the consequences, should she bring the children with her such a great distance and subsequently be unable to find employment. Despite the political situation, Austria and Germany were much closer, and Leander was already well-versed in German.

A second breakthrough, by contemporary measures her international debut, was the world premiere (1936) of Axel an der Himmelstür at the Theater an der Wien in Vienna, directed by Max Hansen. It was a parody on Hollywood and not the least a parody of the German Marlene Dietrich, who had left a Europe marked by Benito Mussolini, Joseph Stalin and Adolf Hitler. It was followed by the Austrian film Premiere, in which she played the role of a successful cabaret star.

The UFA star

![]()

Zarah Leander on the cover of Swedish weekly Se 1941

In 1936, she landed a contract with UFA in Berlin. She became known as an extraordinarily tough negotiator, demanding influence and high salaries with half of her salary paid in Swedish kronor to a bank in Stockholm. Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels dubbed her an "Enemy of Germany", but as a leading film star at UFA, she participated in ten films, most of them great successes. However, unlike other film stars at the time, such as Olga Chekhova, Leander neither socialized with leading party members nor took part in official Nazi party functions. (Both actresses are rumored to have been Communist spies.)

At a party she met the Nazi minister of Propaganda, Joseph Goebbels, who asked her ironically: "Zarah... Isn't this a Jewish name?" "Oh, maybe" the actress told "but what about Josef?" "Hmmm... yes, yes, a good answer" Goebbels replied.

In her films, Zarah Leander repeatedly played the role of a femme fatale, independently minded, beautiful, passionate and self-confident. Although most of her songs had a melancholic flair, some had a frivolous undertext, or could at least be interpreted that way. In 1942, in the midst of a burning war, Leander scored the two biggest hits of her recording career - in her signature deep voice, she sang her anthems of hope and survival: "Davon geht die Welt nicht unter" ('That is not the end of the world') and "Ich weiß, es wird einmal ein Wunder gescheh'n" ('I know that someday a miracle will happen'). These two songs in particular are often included in contemporary documentaries as obvious examples of effective Nazi propaganda at work; however, it should also be noted that Leander's performance on these tracks, along with countless other hits she had all over Europe, struck a chord with the German people. Although no exact record sales numbers exist, it is likely that she was among Europe's best-selling recording artists in the years prior to 1945. Zarah herself was quick to point out in later years that what made her a fortune was indeed not her salary from Ufa, but the royalties from the records she released.[3] "Ich weiß, es wird einmal ein Wunder gescheh'n" was the song on which New Wave singer Nina Hagen (who grew up in the German Democratic Republic (GDR) and as a child had idolized Leander) based her 1983 hit "Zarah".

Return to Sweden

Her last film in Nazi Germany premiered on 3 March 1943. Her villa in the fashionable Berlin suburb of Grunewald was hit in an air raid, and the increasingly desperate Nazis pressured her to apply for German citizenship. At this point she decided to break her contract with Ufa, leave Germany, and retreat to Sweden, where she had bought a mansion at Lönö, not far from Stockholm.

After the Wehrmacht's defeat in the 1943 Battle of Stalingrad, public opinion in Sweden (the government of which remained officially neutral throughout the war, though ideologically aligned with the Allies, but also supplying the Nazis with strategic war materials), was more free to display outward hostility toward the Nazis, especially as news of the Holocaust became widespread[4] (public opinion was mainly anti-Nazi from the start, but was censored in the press by the government, to avoid severe repercussions from Germany). Leander had been far too extensively associated with Nazi propaganda, and as a result was shunned. Gradually she managed to land engagements on the Swedish stage. After the war she did eventually return to tour Germany and Austria, giving concerts, making new records and acting in musicals. Her comeback found an eager audience among pre-war generations who had never forgotten her. She appeared in a number of films and television shows, but she would never regain the popularity she had enjoyed before and into the first years of World War II. In 1981, after having retired from show business, she died in Stockholm of a stroke.

After the war, Zarah Leander was often questioned about her years in Nazi Germany. Though she would willingly talk about her past, she stubbornly rejected allegations of her having had sympathy for the Nazi regime. She claimed that her position as a German film actress merely had been that of an entertainer working to please an enthusiastic audience in a difficult time. She repeatedly described herself as a political idiot. Her fate is similar to that of French operatic singer Germaine Lubin, considered as the greatest French Wagnerian soprano, who had the naivety to sing under the baton of Karajan in Paris, under the German Occupation, and suffered the same accusations and ostracism as did Madame Leander after 1945.

Zarah Leander continued to be very popular in Germany for many decades after World War II. She was interviewed several times in German television until she died.

In 1987 two Swedish musicals were written about Zarah Leander.

In 2003 a bronze statue was placed in Zarah Leander's home town Karlstad, by the Opera house of Värmland where she first began her career. After many years of discussions, the town government accepted this statue on behalf of the first Swedish local Zarah Leander Society. A Zarah Leander museum is open near her mansion outside Norrköping. Every year a scholarship is given to a creative artist in Zarah's tradition. The performer Mattias Enn received the prize in 2010, the female impersonator Jörgen Mulligan in 2009 and Zarah's friend and creator of the museum Brigitte Pettersson in 2008.

Filmography

- 1930 – Dantes mysterier, with Eric Abrahamson, Elisabeth Frisk, Gustaf Lövås

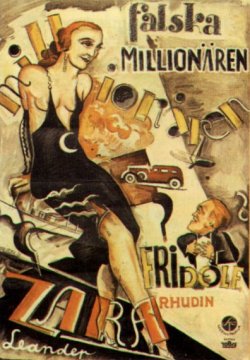

- 1931 – Falska millionären, with Sture Lagerwall, Fridolf Rhudin

- 1935 – Äktenskapsleken, with Einar Axelsson, Karl Gerhard, Elsa Carlsson

- 1937 – Premiere (her first film in German), with Karl Martell, Attila Hörbiger, Theo Lingen

- 1937 – To New Shores, with Willy Birgel, Viktor Staal, Carola Höhn, Erich Ziegel, Hilde von Stolz

- 1937 – La Habanera, with Ferdinand Marian, Karl Martell, Paul Bildt, Edwin Juergenssen, Werner Finck

- 1938 – Heimat, with Heinrich George, Ruth Hellberg, Lina Carstens, Paul Hörbiger, Leo Slezak

- 1938 – Der Blaufuchs, with Willy Birgel, Paul Hörbiger, Jane Tilden, Karl Schönböck, Rudolf Platte

- 1939 – Es war eine rauschende Ballnacht, with Marika Rökk, Paul Dahlke, Aribert Wäscher

- 1939 – Das Lied der Wüste, with Gustav Knuth, Friedrich Domin, Herbert Wilk, Franz Schafheitlin

- 1940 – Das Herz der Königin, with Willy Birgel, Axel von Ambesser, Will Quadflieg, Margot Hielscher

- 1941 – Der Weg ins Freie, with Hans Stüwe, Agnes Windeck, Siegfried Breuer, Hedwig Wangel

- 1942 – Die große Liebe, with Viktor Staal, Paul Hörbiger, Grethe Weiser, Wolfgang Preiss

- 1942 – Damals, with Hans Stüwe, Rossano Brazzi, Karl Martell, Hilde Körber, Otto Graf

- 1950 – Gabriela, with Siegfried Breuer, Carl Raddatz, Grethe Weiser, Gunnar Möller

- 1952 – Cuba Cabana, with O. W. Fischer, Paul Hartmann, Hans Richter, Eduard Linkers, Karl Meixner, Werner Lieven

- 1953 – Ave Maria, with Hans Stüwe, Marianne Hold, Hilde Körber, Berta Drews, Carl Wery

- 1954 – Bei Dir war es immer so schön, with Willi Forst, Heinz Drache, Sonja Ziemann, Margot Hielscher

- 1959 – Der blaue Nachtfalter, with Christian Wolff, Marina Petrowa, Paul Hartmann, Werner Hinz

- 1964 – Das Blaue vom Himmel (TV-Film), with Karin Baal, Toni Sailer, Carlos Werner

- 1966 – Das gewisse Etwas der Frauen, with Nadja Tiller, Anita Ekberg, Romina Power, Robert Hoffmann, Michèle Mercier

Operettas and musicals

- 1931 Franz Lehár, Die lustige Witwe

- 1936 Ralph Benatzky, Axel an der Himmelstür (as Gloria Mills)

- 1958 Ernst Nebhut, Peter Kreuder, Madame Scandaleuse (as Helene)

- 1960 Oscar Straus, Eine Frau, die weiß, was sie will (as Manon Cavallini)

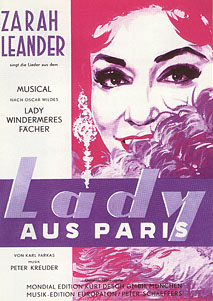

- 1964 Karl Farkas u. Peter Kreuder, Lady aus Paris (as Mrs. Erlynne)

- 1968 Peter Thomas, Ika Schafheitlin, Helmuth Gauer, Wodka für die Königin (as Königin Aureliana)

- 1975 Stephen Sondheim, Hugh Wheeler, Das Lächeln einer Sommernacht (as Madame Armfeldt)

Footnotes

^ Zarah Leander Biography ^ Zarah Leander Biography ^ Leander, Zarah. Zarah's minnen (Zarah's memories). Bonniers publishing, Stockholm (1972) ^ "Sweden". Thanks To Scandinavia. Retrieved 2012-02-27.

References

- Ascheid, Antje. Hitler's heroines : stardom and womanhood in Nazi cinema. Philadelphia, Pa. : Temple University Press, 2003

- Carter, Erica. Dietrich's ghosts : the sublime and the beautiful in Third Reich film. London : BFI Publishing, 2004

- Seiler, Paul. Ich bin eine Stimme. LinkBerlin : Ullstein, 1997

Autobiography

- Es war so wunderbar. Mein Leben. Hamburg: Hoffmann u. Campe. 1973. ISBN 3-455-04090-X

*********************************************************

In a brutalized time and place, one androgyne goddess dared to sing low when she sang love

"Ich bin eine Frau mit Vergangenheit - ich hab' viel erlebt, und hat nichts bereut! " barks a voice like a gelded drill sergeant celebrating a spanking. "I'm a woman with a past; I've lived much, and regretted nothing!" It's a tuneful

"Ich bin eine Frau mit Vergangenheit - ich hab' viel erlebt, und hat nichts bereut! " barks a voice like a gelded drill sergeant celebrating a spanking. "I'm a woman with a past; I've lived much, and regretted nothing!" It's a tuneful

That he had no regrets, " Ich bereue nichts! " was the defiant autobiographical motto of Rudolf Hess. As Hess languished in Spandau prison in East Berlin, an aging star sang those same words, as a woman with a past, in Vienna in 1964. Whether it was telepathy or a fondness for her records, Rudolf Hess knew the lyrics that Zarah Leander enunciated with the overwrought rolled r's of a theatrical Swede, whose German was accented but whose camp was perfect. Born Zarah Stina Hedberg on March 15, 1907 in Karlstad to an organ maker, she grew up with a fascination for music and the stage and was accepted to acting school in Stockholm. Zarah married the Swedish actor Nils Leander in 1927 and toured provincial theaters with Ernst Rolf, the Swedish Ziegfeld, in 1929, exuding glamour and projecting a much-praised "contralto," which referred politely to her bass-baritone. In 1931, Zarah starred as Hanna in impresario Gosta Ekman's Stockholm production of The Merry Widow . Franz Lehar himself saw to transposing the role down two octaves.

When the union with Nils broke up in 1932 and she married Vidar Forsell, son of celebrated Stockholm Royal Opera manager and discoverer of Bj�rling John Forsell, the name had to stay; Zarah Leander was famous. In 1936, Zarah broke into central Europe with a resounding triumph in Ralph Benatzky's operetta Axel an der Himmelst�r (Axel at Heaven's Gate), playing a parody of a Garbo/Dietrich screen idol. Stung by the departures of the real Dietrich and Garbo, the German film conglomerate Ufa signed the new Swede success and undertook a vast advertising campaign to turn a fresh hire into an instant icon. That face and that voice took the Reich by storm with Zarah's second Ufa film, 1937's Zu neuen Ufern (To New Shores), directed by Detlef Sierck (later Hollywood's Douglas Sirk.)

At the Berlin premiere at the baroque UFA-Palast am Zoo, Zarah took over seventy curtain calls. She was a superstar on the spot. Displaying fascism's usual weakness for grasping irony, the Nazi culture machine hired Zarah Leander while she was hamming it up as an ersatz diva and merchandised her as the real thing on movie screens across Europe. In 1936, Zarah was a singing comedienne in Vienna; within two movies and as many years, she was the great tragic lover of the German box office. A staff review in a 1938 issue of Filmwelt praised the newly minted goddess: "This incredibly impeccable and sculptured face mirrors everything that moves a woman: wistfulness and pain, love and bliss, melancholy and resignation. In her attitude as an actress, Zarah Leander is the epitome of 'spiritualized sensuality.' As dark as her low, undefinable alto - which is able to represent so excitingly the expression of hidden female desires - is also her essence." She got fan mail informing "Mr. Leander" that the writer owned all his records, and could he send an autograph. Callers on the telephone demanded repeatedly to speak toFrau Leander, insisting that a man must be at the other end.

The war years were a bizarre romp across the cratered landscape of Nazi propaganda production. Zarah's musical scores were insistently 'racially degenerate'; they overflowed with frowned-upon instruments, like castanets, balalaikas, and stuffed trumpets, and dances such as the habanera, tango, foxtrot and czardas, all from Afro-American and Slavic origins. Out of line with notions of ideal German motherhood, she was typecast as the questing, unlucky-in-love foreigner. (Goebbels drew the ire of Alfred Rosenberg for letting her play a brassy, winning English vaudevillian in Zu neuen Ufern.)

The war years were a bizarre romp across the cratered landscape of Nazi propaganda production. Zarah's musical scores were insistently 'racially degenerate'; they overflowed with frowned-upon instruments, like castanets, balalaikas, and stuffed trumpets, and dances such as the habanera, tango, foxtrot and czardas, all from Afro-American and Slavic origins. Out of line with notions of ideal German motherhood, she was typecast as the questing, unlucky-in-love foreigner. (Goebbels drew the ire of Alfred Rosenberg for letting her play a brassy, winning English vaudevillian in Zu neuen Ufern.)

Zarah refused to be involved with politics, insisting that her job was to entertain, not take sides. The best that can be said of Schwarzkopf and Furtwaengler is that they played along; the worst that can be said of Zarah is that she played dumb. Zarah embodied Nazi glamour. She also traveled to Stockholm in 1938, already an established star, and recorded a jaunty rendition of Sholom Secunda's "Bei mir bist du schoen" only a few years before Charlie and his Orchestra started broadcasting an anti-Semitic Propagandajazz rendition into England, lampooning "the anthem of the international brotherhood of Bolsheviks." As the single best-paid star in wartime Germany, Zarah commanded half a million Reichsmarks for her last three-film deal.

Enjoying the rare privilege of foreign-exchanging two-thirds of her earnings, she invested the money in Sweden, in a house in the south and a fish cannery. She declined German citizenship, refused an estate in East Prussia, and shortly after production wrapped on Damals (1943) and her Berlin home was leveled in air raids, fled to Sweden. The Nazis saw her as a traitor and banned her films; the Swedes gave her a collaborator's icy welcome. Only the Swedish Communist Party embraced her, awarding her a certificate as "a true democrat."

Enjoying the rare privilege of foreign-exchanging two-thirds of her earnings, she invested the money in Sweden, in a house in the south and a fish cannery. She declined German citizenship, refused an estate in East Prussia, and shortly after production wrapped on Damals (1943) and her Berlin home was leveled in air raids, fled to Sweden. The Nazis saw her as a traitor and banned her films; the Swedes gave her a collaborator's icy welcome. Only the Swedish Communist Party embraced her, awarding her a certificate as "a true democrat."

After the war, the Allies banned her from any appearances at all in Germany, associating her intimately with Nazi power. Denied her public for five years, she devoted herself to her fishery business. After having suppressed her as a Nazi, American military intelligence fingered her as a Soviet agent, citing the Communist certificate. There is something here; the Swedish daily Dagens Nyheter reported in 1999 that recently declassified documents from S�PO, the Swedish intelligence service, seem to corroborate the argument that Zarah Leander, self-described "political idiot" and immortal image of fascist glitter, was a Russian spy.

Though her postwar films never recaptured the old totalitarian magic, Zarah resumed a full career on the stage she loved, roaring back onto the scene at the Vienna Raimund-Theater with 1958's Madame Scandaleuse , which Peter Kreuder wrote for her, later touring with it to acclaim in Munich, Hamburg and Berlin. Her voice deepened and gained a guttural edge with age. Listening to a later Zarah song, like the testosterone-laden "Cabaret Paris," it is easy to think of Zarah trapped as a caricature. German critics think her as much, offering patronizing analyses of Zarah reduced to symptom and representation of Nazism.

From the coup with Axel on the Vienna stage in 1936, Zarah seems to have been locked in the cage of a stage farce of stardom rendered genuine. The inexplicable logic of fascism saw fit to make a passing joke into Zarah's half-decade of hegemonic spectacle. Zarah Leander was the most modern of divas: she played a diva in Axel , then was signed to a series of films playing

, and those films' immense popularity reified divadom onscreen into divadom off-. As the years passed, the camp postures multiplied, the gestures grew more outsize, and the androgyny tilted ever manward, even as Zarah fretted about her waning beauty and the gravelly scratches in her voice.

Impenetrable scales, all the more fascinating, alas, as they were the more dangerous, covered the thighs of the Sirens, those daughters of the sea, whose voices are irresistible. D'Aurevilly, Dandyism

Like no other artist, Zarah Leander was a protean product of her art and context. She was never out of date. Her first film, Dante's Mysteries , was 1930 Swedish expressionism barely of a piece with the sound era; her last film was a 1966 sex farce costarring Anita Ekberg. She recorded the Merry Widow Viljalied in 1931; she cut sides of John Lennon's "

" in 1973 and Kris Kristofferson's "Rien ne va plus" in 1977. There was no idiom that Zarah could not seize for her own, dominating it and being dominated in turn. Zarah, not unlike Ronald Reagan, but with more ideals, less senility, and a deeper voice, found her reality molded around the parts she played. She reflected only. Critic Georg Seesslen; unable to decode La Leander, despaired of her as "the falsest woman of the century." Zarah remains a cipher, if for nothing else than the sheer improbability of her life. Imagine the late-era Judy Garland, with the Carnegie Hall Latin orchestrations, taken down an octave, cannily overacted, and commanding a rapt Nazi Europe through the empire of sentiment: thus Zarah. As with Garland, gay audiences have loved, and continue to love, Zarah. Transvestites imitate her adoringly. Nina Hagen has cut tributes to Zarah, letting loose more vibrato than perhaps anywhere else in her oeuvre, and went on to cut

Zarah remains a cipher, if for nothing else than the sheer improbability of her life. Imagine the late-era Judy Garland, with the Carnegie Hall Latin orchestrations, taken down an octave, cannily overacted, and commanding a rapt Nazi Europe through the empire of sentiment: thus Zarah. As with Garland, gay audiences have loved, and continue to love, Zarah. Transvestites imitate her adoringly. Nina Hagen has cut tributes to Zarah, letting loose more vibrato than perhaps anywhere else in her oeuvre, and went on to cut

Zarah protected her favorite songwriter, Bruno Balz, when the Gestapo arrested him in 1942 for "immoral acts" with a lusty Hitler Youth, and Goebbels at last interceded to spare Balz as too valuable for morale to lose. This was not a difficult decision, given Balz's talents; among so many others, he wrote the lusciously memorable " Kann denn Liebe Suende sein?

" ("Can love be a sin?") for Zarah. The real question is that of how, awakened by Zarah's call, a young Hitler Youth's eyes could not be opened to the suppleness of leather jackboots and the transcendent call of love, the more so when love was offered by the greatest songwriter in Germany. Wayne Koestenbaum writes that diva conduct "is a camp style of resistance and self-protection, a way of identifying with other queer people across invisibility and disgrace."Die grosse Zarah , Zarah the Great, was just such resistance and self-protection, a voice in which sexual ambiguity, pride, strength and the maternal caress combined in a sphere of safety. Listening to Zarah sing, it was all right to be gay and to resist while the Swastika flew and the Gestapo roamed the streets.

La Leander, though she may have traded in the lower realms of popular song, belongs to the grand traditions of opera. She shared the screen with Leo Slezak, as he spent his waning days as an Austrian film comedian. She cribbed material from the arias of Gluck, Rossini, and Verdi and the art songs of Tchaikovsky. A perennial late-Zarah favorite is her reading of Cole Porter's " Wunderbar ," which Cesare Siepi also covered. On balance, Siepi has a richer, darker tone, though he hits some higher notes than she does. Siepi, moreover, can never be a diva. His dime-store camp is only the happy accident of a high-test bass doing Cole Porter of the Mantovani "shimmering strings" school. There is nothing in Siepi to hold a candle to Zarah's concluding phrasing, "It's, oy-yoy-yoy-yoy, it's wunderbar!" before the live audience explodes into thunderous applause and foot-stamping.

La Leander, though she may have traded in the lower realms of popular song, belongs to the grand traditions of opera. She shared the screen with Leo Slezak, as he spent his waning days as an Austrian film comedian. She cribbed material from the arias of Gluck, Rossini, and Verdi and the art songs of Tchaikovsky. A perennial late-Zarah favorite is her reading of Cole Porter's " Wunderbar ," which Cesare Siepi also covered. On balance, Siepi has a richer, darker tone, though he hits some higher notes than she does. Siepi, moreover, can never be a diva. His dime-store camp is only the happy accident of a high-test bass doing Cole Porter of the Mantovani "shimmering strings" school. There is nothing in Siepi to hold a candle to Zarah's concluding phrasing, "It's, oy-yoy-yoy-yoy, it's wunderbar!" before the live audience explodes into thunderous applause and foot-stamping.

Popular culture, like Saturn, eats its children. How many theatergoers today remember Eleonora Duse or Alla Nazimova? In 1978, Rolling Stone magazine declared Barry Manilow "the artist of our generation"; within a decade, Barry Manilow was the punch line of the previous. Only opera, a willfully unpopular culture, claws at its stars in the present and reveres them in the past. Callas, Terrence McNally once recalled mournfully to this author, was savaged when she arrived in New York. To read the papers, she was an unseemly woman with an ugly voice. Zarah Leander also suffered to be misunderstood. For the respite she gave to her fans in an era of Grand Guignol come to life, for her privileging of androgyny and camp, and for the irreplaceable

of her voice, she deserves her place in heaven, eyebrow-pencilled, rouged, and lipstick-drenched, at Callas' right hand. There, for posterity, may she be honored as diva and camp-mistress.

Ben Letzler was ejected from backstage at the Met once. His work has been rejected by the journal Commentary and accepted by The Rock , the journal of the Anglo-Catholic Church of Canada.

Source: wikipedia.org

No places

| Relation name | Relation type | Description | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Nils Leanders | Husband | ||

| 2 |  | Adolf Hitler | Friend | |

| 3 |  | Mae West | Coworker | |

| 4 |  | Franco Zeffirelli | Coworker | |

| 5 |  | Fred Bertelmann | Coworker | |

| 6 |  | Marija Leiko | Familiar | |

| 7 |  | Marika Rökk | Familiar | |

| 8 |  | Lya Mara | Idea mate |

No events set